Activity and Recovery - Mental Training

Training the mind doesn’t seem all that different than training the body. The same principles largely apply, though it’s interesting to see how differently we tend to approach working with our minds than we approach training our bodies. For whatever reason, many people hope for optimal mental function by stuffing ever more information in, without considering time for recovery and integration.

Let’s say you were interested in running a fairly long distance – perhaps an event that would take about 2-hours or so. Not the longest running event ever, but definitely not something that could be pulled off simply by mind-over-mattering and gutting through. Preparing for this event would take some training, ideally training that mixed activity with recovery. In training the body, activity balanced by recovery is key to increasing capacity.

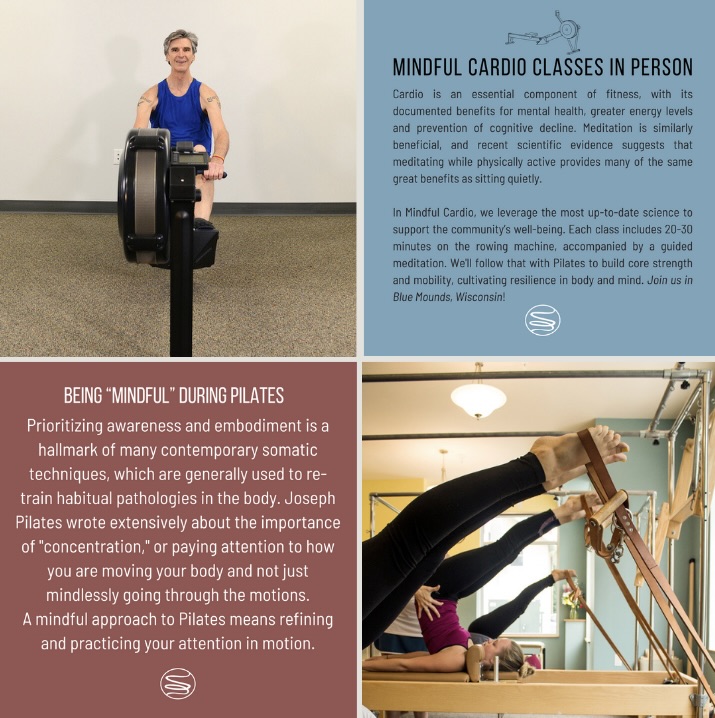

For example, this morning I did my first longish run of the season. The past few months I’ve mainly been working out on the rowing machine, and I’m pleased with the fitness base I maintained through the winter months. That being said, nothing makes for running fitness other than running, and I’ll definitely feel today’s 5+ mile run in the coming days. Rather than layering more and more, slower and slower miles atop today’s fatigue, I plan to do some Pilates tomorrow as part of my active recovery. Then the various fibers that were strained or even slightly damaged by today’s run (a normal part of the process) will have the chance to rebuild – a bit stronger than they were before… and increased capacity will result. The activity provides the benefit, but only when complemented by the recovery.

|

| Is mental training really much different than physical training? |

With our minds, however, we tend to load up our days with junk miles. Junk miles is a term that’s sometimes used for pointless workouts that are unnecessarily long, or for endless workouts that don’t allow for sufficient recovery. And while junk miles are the bane of focused athletic training, they’re the default for how most of us work with our minds. For example, how many of you find yourself taking a mental break by looking at social media, light reading, absentmindedly listening to music or watching TV? Are these activities really giving your mind a break, or just exchanging one form of mental work for another?

These are the questions I’ve been asking myself over the past few months. As I continue preparing for my Ph.D. Preliminary Exams, I’m conscious that I’m asking a lot of my mind. I have hundreds of pages of scientific articles to read, and the exam will likely delve into the details of the specific methods used by the researchers, their statistical analyses, and the strengths and weaknesses of their approaches. The exam is reported to take several days to complete, and I’m approaching the Prelims like I’m training for a mental ultra-marathon.

Like many of us, I habitually pick up a magazine or cue up my favorite podcast when I’m not doing something else. While these are all enjoyable and at least to some extent, potentially enriching activities, they are all pouring more information into my mind. Other than sleep and perhaps my daily meditation time, when do I rest my mind? When do I practice mental recovery?

The past few weeks I’ve operationalized this query by actively embracing boredom. When I finish a study session, I’ve been consciously seeking out boredom – by not listening to the podcasts, reading the magazines or even reading the many great books stacked around my house. I’ve been embracing staring out the window, spending a bit more time on the meditation cushion and otherwise seeking out ways to do nothing. Yes, I’ve experienced boredom, though I’ve also found a spaciousness that’s often elusive. More seems possible, and perhaps more importantly, I don’t feel as harried in executing my daily tasks. There’s a relief in knowing that the day’s interstices are opportunities for mental recovery, rather than the frenzied effort to do something fun or diversionary.

This is an ongoing experiment, and I’m curious to see how balancing mental activity with recovery pans out over the longer haul. In the short-term, I’m pleased to explore the convergence of mental training techniques with what’s known about physical training.

Comments