Sweets and Your Mitochondria

The vitality of your cellular mitochondria are a significant predictor of your health. To support your overall health, it's best to avoid low-fiber foods that are sweet. Fruit is sweet, though is generally high in fiber. A donut, on the other hand, is low in fiber and sweet. The metabolic pathways of each are significantly different, and interact with enzymes in your liver in very different ways.

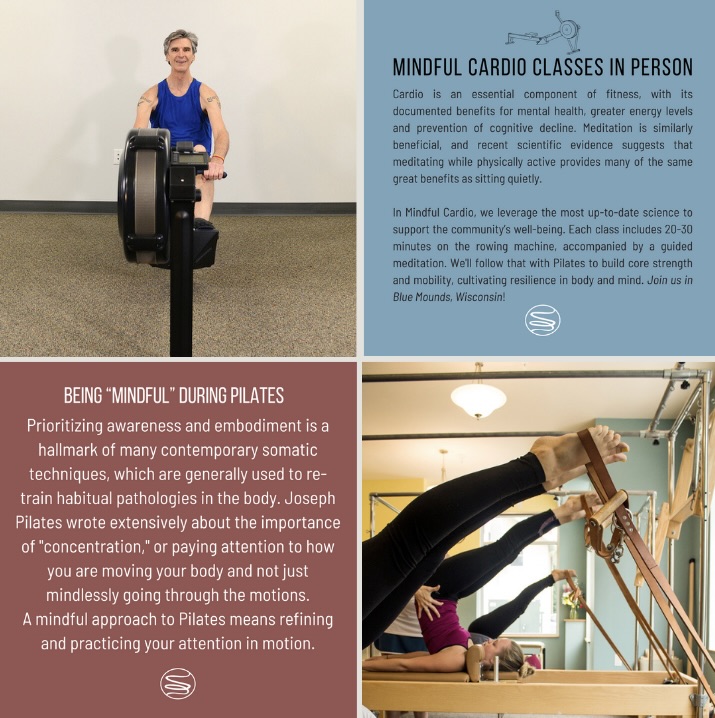

|

| This plant-based donut did not check the whole-foods box |

Metabolic health is your mitochondria working at peak efficiency, and your liver is a mitochondria factory. When you eat low-fiber foods that are sweet, the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in your liver isn't able to bond with the receptors that initiate the production of healthy mitochondria. While your tissues may be crying out for refreshed mitochondria, the factory doors are locked when you consume low-fiber, sweet food.

Not all sweet food is created equal - there are many types of sugars, such as sucrose, fructose, lactose and the various sugar alcohols such as xylitol and sorbitol, to name a few. While their metabolic pathways are all slightly different, there are some common threads. The taste of sweet in your mouth, whether from white sugar, stevia, aspartame or honey, stimulates the sweet-taste receptors. These taste receptors, in turn, catalyze a chain reaction that starts with an insulin surge. Unless sweetness is accompanied by fiber, the insulin-initiated metabolic cascade occurs whether the sweetener is artificial or natural, caloric or non-caloric. Metabolically, there's no free lunch when it comes to sweetness.

The US food system is loaded with added sweeteners, often cloaked by terms such as aspartame, isomalt, maltitol, stevia, hydrogenated starch hydrolysates and so forth. From pasta sauce to salad dressing, most food in the US food supply is both low in fiber and highly sweetened. Even the supposedly healthy foods at stores such as Whole Foods Market or Trader Joe's are often sweetened, albeit with "natural" sweeteners. Unfortunately, your body reacts similarly to sweeteners that aren't accompanied by fiber, whether natural or synthetic, caloric or non-caloric. While it may be tempting to eliminate all added sweeteners, that may not be sustainable over the long haul. The perils of too much sweet food is additive over years, and not the result of a single meal or the occasional donut.

In working with clients, I generally suggest that people start any dietary changes by increasing their consumption of fiber. Rather than ditching the sweet, add fiber. As I've mentioned in previous articles, fiber is the macronutrient I pay attention to the most - more than I pay attention to carbohydrate, fat or protein consumption. Once you're consistently consuming 30+ grams of fiber per day, then experiment with reducing your consumption of sugar.

Your energy levels, metabolism and metabolic health are all dependent upon the vitality of your mitochondria. While there are several levers that you can pull to improve your mitochondrial health, start by increasing your consumption of fiber, then explore decreasing your consumption of sugars. Your mitochondria will return the favor by jump-starting your metabolism and giving you more energy to do what you want and need to do.

Comments